Métis people (Canada)

|

| Total population |

|---|

| 307 845 1.04% of the Canadian population [1] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Languages |

|

English, Métis French, |

| Religion |

|

Predominantly |

| Related ethnic groups |

|

French, Cree, Ojibwa |

| Aboriginal peoples in Canada |

|---|

| First Nations · Inuit · Métis This article is part of a series |

|

History

|

|

Politics

Crown and Aboriginals

Treaties · Health Policy Royal Commission Indian Act · Politics Organizations · Case law Indian Affairs Canada |

|

Culture

Aboriginal cultures

Notable Aboriginals |

|

Demographics

AB (FN, Métis) · Atlantic CA · BC

MB · ON · QC · SK Territories · Pacific Coast |

|

Linguistics

|

|

Religions

Inuit mythology

Traditional beliefs Traditional mythology |

|

Index

Index of articles

Aboriginal · First Nations Inuit · Métis · Stubs |

The Métis (Canadian English: [meɪtiː] Canadian French: [meˈtsɪs] Michif: [mɪˈtʃɪf] ) are an indigenous First People of Canada who trace their descent to mixed European and First Nations parentage. The term was historically a catch-all describing the offspring of any such union, but within generations the culture syncretised into what is today a distinct aboriginal group, with formal recognition equal to that of the Inuit and First Nations. Mothers were often Cree, Ojibway, Algonquin, Saulteaux, Menominee, Mi'kmaq or Maliseet.[3] At one time there was an important distinction between French Métis born of francophone voyageur fathers, and the Anglo Métis or Countryborn descended from Scottish fathers. Today these two cultures have essentially coalesced into one Métis tradition.[4][5] Other former names — many of which are now considered to be offensive — include Bois-Brûlés, Mixed-bloods, Half-breeds, Bungi, Black Scots and Jackatars.[6]

The Métis homeland includes regions in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Newfoundland, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Ontario, as well as the Northwest Territories. The Métis homeland also includes parts of the northern United States (specifically Montana, North Dakota, and northwest Minnesota).[7]

Contents |

Self-identity

Over 300 000 people are self-identified as Métis in Canada. Most Métis people today are not so much the direct result of First Nations and European intermixing any more than English Canadians today are the direct result of intermixing of Saxons and Britons. The majority of Métis who self-identified today are the direct result of Métis intermarrying with Métis. Over the past century, countless Métis are thought to have been absorbed and assimilated into European-Canadian populations making Métis heritage (and thereby aboriginal ancestry) more common than sometimes realized.[8] Geneticists estimate that 50 percent of today's population in Western Canada have Aboriginal blood,[9] and therefore would be classified as Métis by any genetic measure.[9] There is substantial controversy over who qualifies as Métis. Unlike First Nations people, there is no distinction between status and non-status Métis. The legal definition itself is not yet fully developed. S.35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 makes mention of the Métis stating:

- 35(1) The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal people of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

- (2) In this Act, "aboriginal peoples of Canada" includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.[10]

Section-35(2)does not provide a definition of who is Métis. Until R. v. Powley (2003), there was little development in such a definition. The case involved a claim by members of the Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario community asserting Métis hunting rights. The Supreme Court of Canada outlined three broad factors to identify Métis rights-holders:[11]

- self-identification;

- ancestral connection to a historic Métis community; and

- community acceptance.

All three factors must be present for an individual to qualify under the legal definition of Métis, but there is still ambiguity. Whether or not Métis have Treaty Rights is an explosive issue in the Aboriginal world today. Some say that only First Nations could legitimately sign treaties so, by definition, Métis have no Treaty rights.[12] There is one Treaty — the Halfbreed (Métis in the French version) Adhesion to Treaty 3. Descendants of Métis people included in that Treaty clearly have a claim to Treaty Rights. Another Treaty, the Robinson Superior Treaty of 1850, included 84 "half-breeds" in the Treaty.[13] Hundreds, if not thousands, of Métis were initially included in a number of other treaties and then unilaterally excluded under later amendments to the Indian Act.[12] These Métis and their descendants clearly have a claim as well. One judge has agreed that the Manitoba Act, from the point of view of the Métis it addressed, was, in principle, a Treaty.[12] The descendants of those Manitoba Métis clearly have Treaty rights in that context. On September 23, 2003, The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that Métis are in fact a Distinct People with significant Rights.[9]

History

Origins

by Alfred Jacob Miller (1837)

During the height of the North American fur trade in the 1700s and 1800s, many British, Scottish and French-Canadian fur traders married First Nations and Inuit women, mainly First Nations Cree, Ojibwa, or Saulteaux. The majority of this fur traders were French and Catholic.[9] Therefore, their children, the Métis, were exposed to both the Catholic and indigenous belief systems, thus creating a new distinct aboriginal people in North America in the years prior to the colonization of Canada and the United States of America as we know it today. First Nations women were the link between cultures, they not only provided companionship for the fur traders, but also aided in their survival. First Nations women were able to translate the language, sew new clothing for their husbands, and generally were involved in resolving any cultural issues that arose. The First Peoples had survived in the harsh west for thousands of years, so the fur traders benefited greatly from their First Nations wives' knowledge of the land and its resources.[9]

The Métis played a vital role in the success of the western fur trade. Not only were the Métis skilled hunters, but they were also raised to appreciate both Aboriginal and European cultures.[14] Métis understanding of both societies and customs helped bridge cultural gaps, resulting in better trading relationships.[14] The Hudson's Bay Company discouraged unions between their fur traders and First Nations and Inuit woman, while the North West Company (the French fur trading company) supported such marriages.[15] The Métis were valuable employees of both fur trade companies, due to the their skills as voyageurs, buffalo hunters, interpreters and knowledge of the lands.

19th century

In 1812, many immigrants (mainly Scottish farmers) moved to the Red River Valley, in present day Manitoba. The Hudson's Bay Company, who nominally owned the land called Rupert's Land at the time, assigned the land to the settlers.[16] The allocation of Red River land caused conflict with those already living in the area as well as with the North West Company, whose trade routes had been cut in half. Many Métis were working as fur traders with both the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company. Others were working as free traders, or buffalo hunters supplying pemmican to the fur trade.[9] The buffalo were declining in number, and the Métis and First Nations had to go further and further west to hunt them.[17] As well, profits from the fur trade were declining because the Hudson's Bay Company had to extend its reach further and further away from its main posts to get furs.

The Government of Canada exerted its power over the people living in Rupert's Land after its acquisition in the mid-1800s from the Hudson's Bay Company for the railroad.[18] The Métis and the Anglo-Métis (commonly known as Countryborn, children of First Nations women and Orcadian, Scottish or English men),[19] joined forces to stand up for their rights and to protect their age-old way of life against an aggressive and distant Anglo-Saxon government and its local colonizing agents.[16] During this time the Canadian government pressured the Aboriginals to sign treaties (known as the "Numbered treaties") which turned over rights to almost the entire western plains to the Government of Canada. In return for signing over their lands, the Canadian government promised food, education, medical help, and other kinds of support.[20] Emerging as a Métis leader was the educated Louis Riel, who denounced the government in a speech delivered in late August 1869 from the steps of Saint-Boniface Cathedral.[9] The Métis became more fearful when the Canadian government appointed the notoriously anti-French William McDougall as the Lieutenant Governor of the Northwest Territories on September 28, 1869, in anticipation of a formal transfer to take effect in December.[9] What followed was the Red River Rebellion of 1869 and consequently the exile of Louis Riel to the United States.[16]

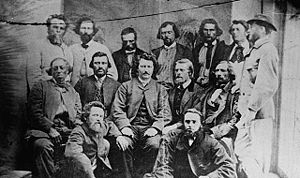

In March 1885, the Métis heard that a contingent of 500 North-West Mounted Police was heading west.[21] They organized a newly formed coalition called The Métis provisional government with Pierre Parenteau as President and Gabriel Dumont as adjutant-general to action. With the help of First Nations Chiefs Poundmaker and Big Bear they facilitated the return of Louis Riel to the coalition he founded in 1869. This led to a series of unsuccessful conflicts collectively known as the "Riel Rebellions" or the North West Rebellion.[16] Gabriel Dumont fled to the United States with Louis Riel, Poundmaker and Big Bear surrendering to the Government. Big Bear and Poundmaker each received a three-year sentence. On July 6, 1885, Riel was charged with high treason and was sentenced to hang. Riel's appeals went on briefly, but, as mandated by the government of the time, the execution was conducted on November 16, 1885.[16]

20th century

During the 1930s, political activism arose in Métis communities in Alberta and Saskatchewan over land rights. Five men, sometimes dubbed "The Famous Five", (James Patrick Brady, Malcolm Norris, Peter Tomkins Jr., Joe Dion, Felix Callihoo) were instrumental in having the Alberta government hold the "Ewing Commission" in 1934 dealing with land claims.[22] The Alberta government would pass the Métis Population Betterment Act in 1938.[22] The Act provided funding and land to the Métis (The provincial government later rescind portions of the land in certain areas).[22]

The 1960s saw the emergence of renewed political organizations. The "Alberta Federation of Métis Settlement Associations" was established in the mid 1970s and provides a collective voice for the Métis Nation of Alberta.[22] During the constitutional talks of 1989, the Métis were recognized as one of the three Aboriginal peoples of Canada. In 1990, land titles passed from the Alberta government to Métis communities through the "Métis Settlement Act", replacing the Métis Betterment Act.[22]

The position of Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians was created in 1985 as a portfolio in the Canadian Cabinet.[23] As the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development is officially responsible only for Status Indians and largely with those living on Indian reserves, the new position was created in order provide a liaison between the federal government and Métis and non-status Aboriginal peoples, urban Aboriginals and their representatives.[23]

In 2007, Conservative Chuck Strahl became both Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (Canada) and Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians in the government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

Organizations

The Provisional Government of Saskatchewan was the name given by Louis Riel to the independent state he declared during the Northwest Rebellion of 1885 in what is today the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The governing council was named the Exovedate, Latin for "of the flock", and debated issues ranging from military policy to local bylaws and theological issues. It met at Batoche, Saskatchewan, and only exercised real authority during its existence over the Southbranch Settlement. The provisional government collapsed that year after the Battle of Batoche.

The Métis National Council was formed in 1983, following the recognition of the Métis as an aboriginal people in Canada, in Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The Métis National Council is composed of five provincial Métis organizations, Ontario having the least number of votes.[24] They are:

- Métis Nation British Columbia

- Métis Nation of Alberta

- Métis Nation - Saskatchewan

- Manitoba Métis Federation

- Métis Nation of Ontario.

The Métis people mandate these governance structures through province-wide ballot box elections held at regular intervals for regional and provincial leadership. Further, Métis citizens and their communities are represented and participate in these Métis governance structures by way of elected Locals or Community Councils, as well as, provincial assemblies held annually.[25]

Culture

- See also: Notable Métis people of Canada

Language

A majority of the Métis once spoke, and many still speak, either Métis French or a mixed language called Michif. Michif, Mechif or Métchif is a phonetic spelling of the Métis pronunciation of Métif, a variant of Métis.[26] The Métis today predominantly speak French, with English a strong second language, as well as numerous Aboriginal tongues.[27] Métis French is best preserved in Canada, Michif in the United States, notably in the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation of North Dakota, where Michif is the official language of the Métis that reside on this Chippewa reservation.[28] The encouragement and use of Métis French and Michif is growing due to outreach within the provincial Métis councils after at least a generation of decline.[29]

The 19th Century community of Anglo-Métis, more commonly known as Countryborn, were children of Rupert's Land fur trade ; typically of Orcadian, Scottish, or English paternal descent and Aboriginal maternal descent.[30] Their first languages would have been Aboriginal (Cree language, Saulteaux language, Assiniboine language, etc.) and English. It seems likely that their fathers spoke Gaelic, thus leading to the development of the dialect of English referred to as "Bungee".[31]

Flag

The Métis Flag is one of the oldest patriotic flags originating in Canada.[32] The Métis actually had two flags. Both flags had the same design, an infinity sign, but were different colours, either red or blue. Red was the colour of the Hudson's Bay Company, while blue was the colour of the North West Company.[32]

Distinction of lower-case 'm' versus upper-case 'M'

The term Métis was originally used to refer children from the union of Frenchmen and Native women. The first records of "Métis" are shown as early as 1600 on the East coast of Canada. Later the movement of the fur trade brought about more unions between French and Cree. Descendants of English or Scottish and natives were historically called 'half-breeds' or 'country born' and lived a more agrarian and Protestant lifestyle.[33] The term eventually evolved to refer to all 'half-breeds', whether linked to the historic Red River Métis or not.

Lower case 'm' métis refers to those who are of mixed native and other ancestry, and is essentially an ethnic definition. Capital 'M' Métis refers to a particular sociocultural heritage and an ethnic self-identification that is not entirely racially based.[34] Some argue that people who identify as métis should not be included in the definition of 'Métis'. In fact, not all such people might meet the legal test. Others have gone further and have suggested that only the descendants of the Red River Métis should be constitutionally recognized.[35] The effect of this limitation would mean that people such as the some of the Labrador, Quebec, and Ontario Métis would be excluded from the legal definition and relegated to little 'm' métis status.

See also

- Métis people (United States)

- Metis Child and Family Services Society

- Vancouver Métis Community Association

- Exovedate

- Bell of Batoche

- Battle of Cut Knife

- Battle of Duck Lake

- Battle of Fish Creek

- Battle of Fort Pitt

- Battle of Frenchman's Butte

- Frog Lake Massacre

- Battle of Loon Lake

- Looting of Battleford

- Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography

- List of Métis people

References

- ↑ [1] Statistics Canada, Census 2001—Selected Ethnic Origins1, for Canada, Provinces and Territories—20% Sample Data

- ↑ [2] (Statistics Canada, Census 2001—Selected Demographic and Cultural Characteristics (105), Selected Ethnic Groups (100), Age Groups (6), Sex (3) and Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories and Census Metropolitan Areas 1 , 2001 Census—20% Sample Data)

- ↑ "First Nations Culture Areas Index". the Canadian Museum of Civilization. http://www.civilization.ca/cmc/exhibitions/tresors/ethno/etb0170e.shtml.

- ↑ Ethno-Cultural and Aboriginal Groups

- ↑ Rinella, Steven. 2008. American Buffalo: In Search of A Lost Icon. NY: Spiegel and Grau.

- ↑ McNab, David; Lischke, Ute (2005). Walking a Tightrope: Aboriginal People and their Representations. http://books.google.ca/books?id=YMdYqTvG3EgC&pg=PA254&lpg=PA254&dq=jackatar&source=bl&ots=HrRp9CcSTx&sig=N6G2T7IN8pAWsMbB5nlWZ5i8dJc&hl=en&ei=tPeCS6iXO5CYtgfEo53wBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=9&ved=0CB0Q6AEwCA#v=onepage&q=jackatar&f=false.

- ↑ Howard, James H. 1965. The Plains-Ojibwa or Bungi: hunters and warriors of the Northern Prairies with special reference to the Turtle Mountain band. University of South Dakota Museum Anthropology Papers 1 (Lincoln, Nebraska: J. and L. Reprint Co., Reprints in Anthropology 7, 1977).

- ↑ Barkwell, Lawrence J., Leah Dorion and Darren Préfontaine. Métis Legacy: A Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Winnipeg: Pemmican Publications Inc. and Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute, 2001. ISBN 1-894717-03-1

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 "Complete History of the Canadian Metis Culturework=Metis nation of the North West". http://www.telusplanet.net/public/dgarneau/metis.htm.

- ↑ "Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms". department of justice canada. http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/const/annex_e.html#II.

- ↑ (2003), 230 D.L.R. (4th) 1, 308 N.R. 201, 2003 SCC 43 [Powley]

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 McNab, David, and Ute Lischke. The Long Journey of a Forgotten People Métis Identities and Family Histories. Waterloo, Ont: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-88920-523-9

- ↑ Morris, Alexander. The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba and the North West Territories Including the Negotiations on which They Were. Published 1880 by Belfords, Clarke & Co.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "The Metis Nation". Angelhair. http://www.geocities.com/soHo/Atrium/4832/metis.html.

- ↑ "Who are the METIS? work=Métis National Council". http://www.metisnation.ca/who/index.html.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 "Riel and the Metis people". The departments of Advanced Education and Literacy, Competitiveness, Training and Trade, and Education, Citizenship and Youth. http://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/iru/library_publications/bibliographies/louis_riel-02-2008.pdf.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Metis People". Wolf Lodge Cultural Foundation ~ Golden Braid Ministries. http://www.wolflodge.org/visibiliti/metis/history.htm.

- ↑ Gillespie, Greg (2007). Hunting for Empire Narrative of Sport in Rupert's Land, 1840-70. Vancouver, BC, Canada: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-1354-9

- ↑ Jackson, John C. Children of the Fur Trade Forgotten Metis of the Pacific Northwest. Corvallis: Oregon State Univ Press, 2007. ISBN 0-87071-194-6

- ↑ "Numbered Treaty Overview". Canadiana.org (Formerly Canadian Institute for Historical Microreproductions). Canada in the Making. http://www.canadiana.org/citm/specifique/numtreatyoverview_e.html. Retrieved 2009-11-16. "The Numbered Treaties - also called the Land Cession or Post-Confederation Treaties - were signed between 1871 and 1921, and granted the federal government large tracts of land throughout the Prairies, Canadian North and Northwestern Ontario for white settlement and industrial use. In exchange for the land, Canada promised to give the Aboriginal peoples various items: cash, blankets, tools, farming supplies, and so on. The impact of these treaties can be still felt in modern times."

- ↑ Weinstein, John. Quiet Revolution West The Rebirth of Métis Nationalism. Calgary: Fifth House Publishers, 2007. ISBN 978-1-897252-21-5

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 "The Métis" (rtf). Canada in the Making. 2005. http://www.canadiana.org/citm/specifique/metis_e.rtf. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Office of the Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians (Mandate, Roles and Responsibilities)". Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. 2009. http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/ai/arp/mrr-eng.asp. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ National Council of Welfare (Canada), and Michelle M. Mann. First Nations, Métis and Inuit Children and Youth Time to Act. National Council of Welfare reports, v. #127. Ottawa: National Council of Welfare, 2007. ISBN 978-0-662-46640-6

- ↑ "Métis National Council Online". MÉTIS NATIONAL COUNCIL. http://www.metisnation.ca/.

- ↑ *Barkwell, Lawrence J. "Michif Language Resources: An Annotated Bibliography." Winnipeg, Louis Riel Institute, 2002. See also www.metismuseum.com

- ↑ "Fast Facts on Metis". Metis Culture & Heritage Resource Centre. http://www.metisresourcecentre.mb.ca/fastfacts/.

- ↑ "The Michif language". Metis Culture & Heritage Resource Centre. http://www.metisresourcecentre.mb.ca/language/language.htm.

- ↑ Barkwell, Lawrence J., Leah Dorion, and Audreen Hourie. Metis legacy Michif culture, heritage, and folkways. Metis legacy series, v. 2. Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute, 2006. ISBN 0-920915-80-9

- ↑ Barkwell, Lawrence J., Leah Dorion, and Audreen Hourie. Metis legacy Michif culture, heritage, and folkways. Metis legacy series, v. 2. Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute, 2006. ISBN 0-920915-80-9

- ↑ Blain, Eleanor M. (1994). The Red River dialect. Winnipeg: Wuerz Publishing.Bungee (Canadian Encyclopedia)| accessdate =2009-10-06

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "The Metis flag". Gabriel Dumont Institute(Metis Culture & Heritage Resource Centre). http://www.metisresourcecentre.mb.ca/history/flag.htm.

- ↑ . E. Foster, "The Métis: The People and the Term" (1978) 3 Prairie Forum 79 at 86-87.107

- ↑ J. Brown, "Métis", Canadian Encyclopedia, vol. 2 (Edmonton: Hurtig, 1985) at 1124.

- ↑ Paul L.A.H. Chartrand & John Giokas, "Defining 'the Métis People': The Hard Case of Canadian Aboriginal Law" in Paul L.A.H. Chartrand, ed., Who Are Canada's Aboriginal Peoples?: Recognition, Definition, and Jurisdiction, (Saskatoon: Purich, 2002) 268 at 294

Further reading

- Barkwell, Lawrence J., Leah Dorion, and Audreen Hourie. Metis legacy Michif culture, heritage, and folkways. Metis legacy series, v. 2. Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute, 2006. ISBN 0-920915-80-9

- Barnholden, Michael. (2009). Circumstances Alter Photographs: Captain James Peters' Reports from the War of 1885. Vancouver, BC: Talonbooks. ISBN 978-0-88922-621-0.

- Dumont, Gabriel. GABRIEL DUMONT SPEAKS. Talonbooks, 2009. ISBN 978-0-88922-625-8.

External links

|

|

- Government of Canada

- Aboriginal Canada Portal

- Canadian Genealogy Centre

- Congress of Aboriginal Peoples

- Differing Criteria for Métis

- Métis—The Kids' Site of Canadian Settlement

- Métis National Council Historical Online Database

- Other

- A History of Aboriginal Treaties and Relations in Canada Site includes contextual materials, links to digitized primary sources and summaries of primary source documents.

- Métis Museum (Gabriel Dumont Institute)

- MiLan Metis Healing Art Project—MMHAP

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)